I was late to my first day of class. My prospects of making

a good impression with the teacher decreased dramatically every time I ran up

to a building only to discover that the class was no longer where it should be. The community college is a campus of buildings spread across small hills. The hills

I was late to my first day of class. My prospects of making

a good impression with the teacher decreased dramatically every time I ran up

to a building only to discover that the class was no longer where it should be. The community college is a campus of buildings spread across small hills. The hills aren’t big or particularly challenging, except

when you are late for a class you are hoping to add. Then it seems everywhere

you go, you are either going up a hill or down one.

For the second time that morning, I climbed the steps to the student services building to get some help. This wasn’t the first time I’ve

been to the campus or taken a class here, but a few years have passed, and I hardly recognized the school. Large areas, once rolling swaths of grass, were now cut up and fenced off with eight foot high

cyclone fences, which gave you a sense of walking through a zoo rather than a school. Everywhere

I turned seemed to be in some state of construction. A brand new fine arts

building unexpectedly appeared before me. I then passed another new building,

almost complete. A construction worker called down to his co-worker who yelled

back over the din of jackhammers below. Students were scattered, milling around the bookstore,

either reading their textbooks or talking to classmates sitting on the weathered

wood benches, or gathered around the short adobe-like walls that

carved out small patches of green turf and surrounded the large oak and walnut trees.

I was told the creative writing class was in another

building located in another area of the campus. This time, further east, near

the parking lot, in one of the older buildings. I climbed yet another hill. Rather this time, it was concrete

ramp, leading to a row of classrooms. The 70’s single story, flat-roofed building

was unremarkable, except for its stark contrast to the newest building across

the campus, jutting forth above the trees, like a trumpet pointing upward, as

if to herald its arrival. Around the corner I heard the dripping of water and

wondered, when did it rain? It didn’t. I

obeyed the cautionary signs and watched my step.

By the time I reached the classroom, the right one this time, class was nearly over. My abrupt entrance interrupted the teacher, who had been in

the middle of reading a poem out loud. He pushed his glasses up his nose to look at me. I recognized him immediately. I'd taken his class a number of years ago. Other than a few more

wrinkles and a little more gray, he was the same as I remembered. Out of nervousness, I blurted out that I wanted

to add his class.

The teacher asked, “Do you know where you are?”

I answered with a yes, but his question took me off guard. I

reflexively looked around. Did I know where I was? The room was small and somewhat cramped. The L-shaped student desks were jammed so close together, there hardly seemed any

space between them. A dampness clung to the air. The black built-in bookshelves

on the back wall were empty, which seemed sad to me, especially for a creative

writing class, but there was also a part of me that appreciated the irony of

it. Writing students sat elbow to elbow,

staring at me. I felt the heat rising underneath my shirt, and now wished I hadn’t grabbed the down jacket in my haste earlier that morning.

“Do you like to read poems and short stories?” The teacher

asked.

“I do.” Of course I do, I thought. I had the student loans

to prove it.

“Do you like to write

poems and short stories?"

“I do,” I said, except my voice wavered slightly. When was

the last time I actually wrote a poem?

“First take a seat and see if by the end of the class you really

want to be here.”

I took one of the seats that was off to the side, like a

chair in time-out.

I ended up sitting

next to someone else who wanted to add the class. The teacher resumed his

lesson, and I shifted into a “writerly” state of mind. I eased back against the

hard, wooden chair, and listened to my classmates deconstruct a

Billy Collins poem.

To be quite honest, I was back in community college,

taking a writing class in order to force myself to write. It turns out I’d written more in one semester of grad school than I have in the five years after getting my MFA. My focus had since turned to

publishing and my creative outlets were replaced more and more with design,

mainly book design.

At the end of the class, the teacher gave me my first assignment,

which was to write an edible poem or a poem with a sense of place. I chose the

latter because I wrote an edible poem the last time I took the class several years ago (which you can read on

Fictionaut). In trying to come up with a place to write about, I

realized that one of the first things I want to know before designing a book cover is where the story is taking place.

I often go

into bookstores or stores with book departments to check out the latest book

covers.

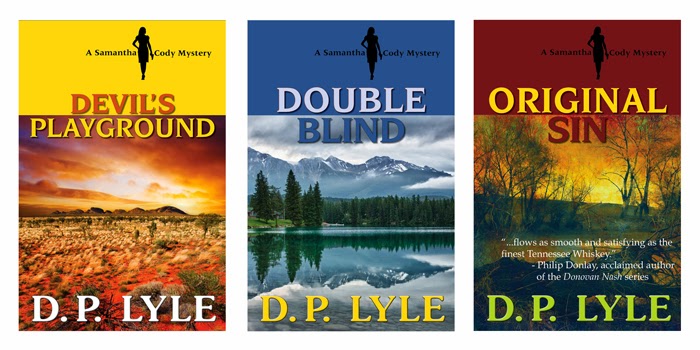

Many books I found, especially genre

fiction, evoke a sense of place on their covers.

A sense of place can pull you into the story and place you inside a character's point of view:

My house was at the very tip of the egg, only fifty yards

from the Sound, and squeezed between two huge places that rented for twelve or

fifteen thousand a season. The one on my right was a colossal affair by any

standard-it was a factual imitation of some Hôtel de Ville in Normandy, with a

tower on one side, spanking new under a thin beard of raw ivy, and a marble

swimming pool, more than forty acres of lawn and garden. It was Gatsby’s

mansion.

-F. Scott Fitzgerald, from The Great Gatsby

Fitzgerald grounds the scene and situates the narrator with specific, concrete imagery. I’ve never been to a Hôtel de Ville in Normady, but I almost feel I’d recognize Gatsby's sprawling grounds and ostentatious mansion if I did.

Setting or a sense of place doesn’t have to be static

either:

If on leaving town you take the church road you soon will

pass a glaring hill of bonywhite slabs and brown burned flowers; this is the

Baptist cemetery. Our people, Talbos, Fenwicks, are buried there; my mother

lies next to my father, and the graves of kinfolk, twenty or more, are around them like the prone roots of a stony tree. Below the hill grows a field of high

Indian grass that changes color with the seasons; go see it in the fall, late

September, when it has gone red as sunset, when scarlet shadows like firelight

breeze over it and the autumn winds strum on its dry leaves sighing human

music, a harp of voices.

I love the forward movement, like a camera lens moving,

recording the landscape it encounters. It feels multi-dimensional and teeming

with color. Capote adds texture with an

element of sound. He also includes

character background, history and uses direct address to pull the reader in

further.

For the class assignment, I ended up writing a poem about

Kauai, but as I wrote it, I wondered if readers would think it was Florida, so

I narrowed the focus, bringing it down to road-level and kept moving as if the reader

and I were making our way through the tropical trail, then pulling the narrative lens up for

a grander sense of the place, a bird’s eye view. I even titled the poem “Bird

Island.”

When I handed in the poem, I felt a sort of anxious acceptance. It has been a while

since I’ve written something to share with someone else other than my cats. And it

was in that moment, in that classroom with other writers reading, writing, and

sharing, when I fully understood the teacher’s earlier questions. Yes, I know where I am now. I am exactly where

I should be.